Endometriosis, firsthand.

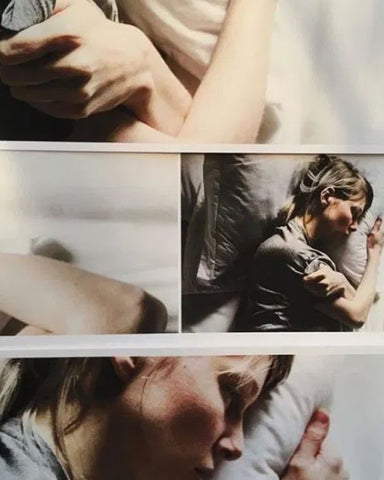

“Endometriosis is an intrusive roommate”, says psychologist and photographer Chiara Scattina, who is affected with endometriosis.

Index:

What do you want to tell me today in order to break the silence?

Chiara, how would you explain endometriosis to someone who doesn’t suffer from, or isn’t familiar with it?

You rightly defined the disease as “debilitating” and “silent”. What is being done for endometriosis in Italy?

How did you find out you had endometriosis?

I would expect specialists to devote their attention towards helping women better manage their intimacy. Am I wrong to assume this?

Chiara, is there someone who inspires you or has given you strength?

Are there any symptoms or other signals to look out for?

I wanted to close off the article series by looking at this disease through a firsthand account of the experience—a voice that can help us understand what it truly means to be affected with endometriosis. The disease doesn’t just involve having “simple” menstrual cramps—and by the way, there’s nothing “simple” or normal about menstrual cramps.

What do you want to tell me today in order to break the silence?

I want to turn to those who dismiss women finding themselves being forced to take sick days or holiday time in order to travel to specialised centers far away from home. I want turn to those who tell us that we’re just stressed and that we need to calm down, or that endometriosis will pass. I want to speak out against those who—even if they are doctors or gynaecologists—don’t have the necessary skills to effectively diagnose endometriosis. And instead of sending us to their colleagues who are specialised, they leave us in “limbo”, filled with doubts and unsuitable therapies.

I want to turn to those who tell us that “we all have menstrual pain”, and that it takes only two or three days of being patient before it passes. I want to turn to those who have put hormonal therapies on the market in order help “maintain” the situation, but price their services absurdly high, making it unattainable for all women. I want to turn to those who diminish the severity of the disease, and to those who don’t understand that a disease affecting women’s reproductive organs affects all of us, because it can also be the cause of infertility or being unable to complete a pregnancy.

So, there you have it. I’m turning to you and I’m telling you: listen to us, inform yourselves.

Chiara, how would you explain endometriosis to someone who doesn’t suffer from, or isn’t familiar with it?

It’s a chronic, debilitating disease that affects 3 million women (1 in 10) in just Italy. Both the cause and the cure for the disease are unknown. What is known, however, is that the endometrial tissue present in the uterus (the one that flakes off and leads to menstruation) is not completely expelled. Instead, it goes back up to the ovaries, the uterus, tubes, and even the intestine, bladder, kidneys, lungs or nerves.

The consequences? Cysts, chronic inflammation of the organs where the foci of the endometrium are implanted, scars, distortion regarding anatomical relationships of certain organs, adhesions—and in some cases, fertility.

Aches and pain. A lot of discomfort, chronic fatigue, and having to constantly resort to surgery and/or hormonal therapies in order to keep it at bay. We know that the concept of “pain” can come in all shapes and sizes.

As a psychologist, I’m in touch with things like trauma, grief, separation, or not accepting oneself or something. I’m aware of the fact that something can always be done—that pain can be processed and overcome.

But chronic pain does not let you go.

I carry it with me in my lap—literally—because that is where endometriosis comes from, and from where it can continue to expand. Sometimes it’s dull, other times it’s acute, and other times still it’s an atrocious burning. In some cases it’s colic, in others it’s subocclusion, or in other cases it’s a migraine. Sometimes it breaks your legs, or it makes you squirm and hope that once and for all—it will pass.

As I listened to Chiara, I thought about how strong these women are, not only because they are battling a difficult disease, but because the disease they are battling is almost “invisible” and silent. No one knows how to cure it, and no one talks about it.

You rightly defined the disease as “debilitating” and “silent”. What is being done for endometriosis in Italy?

Thanks to the fight carried out by women suffering from the disease, since 2017, endometriosis has returned to the new Essential Assistance Levels (LEA) as a “debilitating chronic disease”. It’s labeled as chronic because it is possible to treat the symptoms, but not to cure the disease. It’s debilitating because one’s quality of life suffers on several sides, including private and social lives along with work and psychological sides, either because of the interventions needed or the strong pelvic pain.

The pain can be so excruciating that it’s impossible to carry out one’s normal daily activities, and it can make basic bodily functions or sexual relations very difficult. This is all complicated by the fact that there is still substantial reservation laced with misinformation when it comes to the menstrual cycle.

– Let’s just say it: it’s still a taboo subject. Just think about the fact that TV commercials still show blue liquids for sanitary napkins. Blood and menstruation are still things that need to be “hidden”.

We’ve grown up with the cliché that menstruation is painful, and that’s that. What’s more, is that endometriosis is “invisible” and silent, and therefore stigmatised because what is not seen seems inexistent. So, even if we try not to let the disease beat us down or immobilise us, we find ourselves fighting to get better and fighting for our condition to be recognised.

Obviously, the silence, the taboo on the subject, and the objective difficulties in recognising the disease often lead to a difficult and psychologically draining “pilgrimage” of sorts when looking for answers.

How did you find out you had endometriosis?

Arriving to the final diagnosis of endometriosis is not at all simple. This is because very often, gynaecologists fail to recognise it if they aren’t specialised in that specific pathology. Unfortunately, these same gynaecologists tell us that having menstrual pain is normal, and that we’re healthy. This creates many problems because a delay in the final diagnosis can lead to severe aggravation, and runs the risk of compromising the natural functionality of some organs, such as the colon or bladder.

I was “lucky” in that I didn’t have a late diagnosis. When I was 20 years old, my endometriotic cysts, which the birth control pill had kept at bay for years, were easily identified with a simple ultrasound.

________________________________________________________________

You may also like: Endometriosis, Pain and Sex

________________________________________________________________

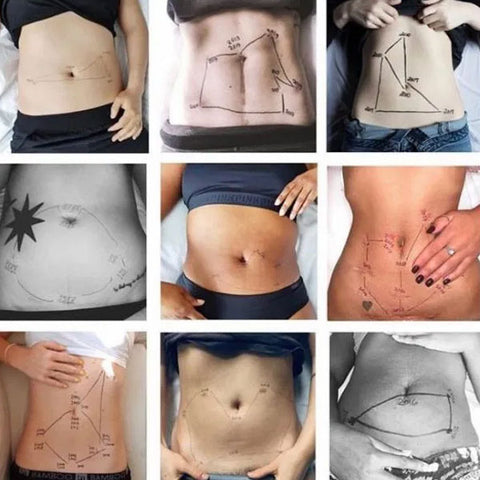

However, the situation was triggered when I stopped taking the birth control pill in the hopes of getting pregnant, and the cramps continued well after the menstruation days. I listened to my body and understood that I had to see a specialised doctor in order to have a more comprehensive and clear picture of the situation. This is how I realised that I had not only cysts in my ovaries, but also an adenomyosis in the uterus and two nodules infiltrating the rectum wall.

The psycho-physical burden is important, because we have to invest so much energy and economic resources in reaching a correct diagnosis and in trusting specialists who are competent. There are very few centers of excellence in Italy— as in every country – hence the phenomenon of medical tourism and the “pilgrimage of pain” that people go through in order to find the “right” specialist.

Speaking of specialists, I talked with Chiara regarding the relationship between illness and sexuality, which is another huge taboo. Sexuality is a fundamental part of any person, regardless of his or her physical condition. Unfortunately, this can be extremely underestimated once someone is struck with this disease.

In this sense, endometriosis is particularly intrusive, so I would expect specialists to devote their attention towards helping women better manage their intimacy. Am I wrong to assume this?

Speaking only from experience with my current gynaecologist when reaching a diagnosis, I was asked if sexual acts were painful for me. And often it is painful—pain is present even in intimate moments, further burdening the psycho-physical pain for a woman, and consequently, for the couple.

Unfortunately, however, no—this aspect is not explored nor is it given much attention, if it doesn’t involve the moment in which one has difficulty conceiving naturally. So, the focus is more or less comprised by pathology, and leans more towards infertility, maternity, and procreation rather than sexuality and sexual pleasure.

I think that it’s fundamental to involve one’s partner in this, so as not to fall into a rut of self-deception, or thinking that it’s a fault to be ashamed of. My partner and I attempted PMA (medically assisted procreation), which contains a “natural aspect” that people imagine to be missing in conception, to make room for hormonal dosages, shots in the belly, and unnerving expectations. However, our strength has been remaining complicit and united in this front as well.

In many countries, it’s unfortunately normal to believe that a link between illness and sexuality is irrelevant—this doesn’t just happen in Italy. In fact, it makes me think of Lena Dunham, an American director, who also has endometriosis and frequently posts about this idea that exists in many countries.

Chiara, is there someone who inspires you or has given you strength?

Rather than just thinking of one “role model”, I think about all of the women who have been fighting for change, for us and for future generations, for much longer than I have. I was inspired and motivated by the worldwide march for endometriosis, which was held in Rome last year. (It’s 6 years the march is done globally).

I’ve decided to give a concrete contribution in terms of support, information, and bringing awareness to endometriosis. I’ve wanted to do this so much, and it’s finally happening thanks to a self-help group called SostenEndo that I’ve moderated since last year. The way I see it, the women I’ve come to know are role models in the way that they face their days, their surgeries, their therapies, their pain, and their psycho-physical fatigue. The network that we’ve created goes far beyond simply sharing a common feeling. It’s a true sisterhood. (Similar groups and association for UK readers here)

I think it’s extremely important to understand the experiences of other women as well. Earlier you mentioned having chronic pain. Are there any symptoms or other signals to look out for?

It’s not fair to generalise, since every woman is different, but if menstrual pains are very strong, it’s certainly a good idea to understand why. In particular, I think this is most important for very young girls and their parents, because they can perhaps arrive to the correct diagnosis much quicker than our generation has.

Let’s break the silence that revolves around the menstrual cycle. Let’s talk about how we are, and let’s stop believing in the stereotype that menstruation should be painful. Let’s demand that people listen to us and respect what we have to say.

Activate that emotional intelligence that could help us move forward. Which emotional intelligence, you ask? That which provides more empathy from hospital personnel and staff, decreases waiting lists and increases more specialised centers, especially in those areas, where they are already scarce.

It also involves a greater responsibility from institutions and the Ministry of Health, in terms of exemptions and protections. Fortunately, associations are able to make up for this by spreading information and creating awareness campaigns and support groups, along with providing psychological support and funding scientific research. Despite this, there is still so much to do and to say. We are not giving up.

And we will continue to give a voice to Chiara and to all women who want to break the silence.